Today (Tuesday 28th September 2010) is the 90th birthday of one of Britain's most esteemed artists. Alan Davie first made an impact with his unique brand of abstract painting in the late 1940s and the Cecil Higgins Art Gallery first acquired one of his works in 1959 - and not without controversy, but more on that later. A further work was purchased in the 1970s, but after the release of the 2004 Cecil Higgins Art Gallery Print Catalogue, Davie donated a major collection of his print and gouache works to the gallery.

Over the next few days you'll be able to view all of the works in our collection by Davie, get an insight into his print making process, and read the fascinating debate provoked by the Gallery's 1959 purchase of 'First Movement in Pink'.

UPDATE: Alan Davie Collection now viewable here

First we'll start with a biography of the artist.

Broad Horizons: Alan Davie (1920- )

Alan Davie's experience of the Second World War was unusual. Having left his home town of Grangemouth, Scotland, a year earlier to take an entrance scholarship to study at the Edinburgh College of art, he had been sent to join the Royal Artillery in the middle of the English countryside. Instead of discovering, as many did, the harsh realities of war, Davie discovered nature, drew his fellow gunner-men, and planted a garden. His eyes were opened to a new way of life - one where the quality of ones existence was of the utmost importance.

Davie turned his back on painting to be a jazz musician after the war, as this seemed a better way to achieve what he wanted from life. Again, it was travel that opened his eyes to new possibilities. In 1948 he finally took up a traveling scholarship awarded at Edinburgh and went with his wife, Bili, who he had married in 1946, to Venice. The city was then hosting the first Biennale since the war. The great art collector Peggy Guggenheim had been given use of a tent originally allocated to Greece, then in civil war. Seeing the Surrealist works of Max Ernst and Joan Miro, and the early mythological paintings of the American artists Pollock, Rothko, Gorky and Matta had a profound effect on Davie: these pictures, steeped in Jungian theory of the universal unconscious, and with mythological names and references, showed Davie new possibilities in the purpose of painting. He re-started work immediately and was instantly well received when within a short space of time he held an exhibition in Venice. By the the time he returned to England, he had already established a reputation as an artist.

Throughout the next few years hes painting was accompanied by work as a goldsmith, silversmith and jeweller. He was inspired by American, Celtic and Syrian goldwork. In 1959 this new direction led him to become a jewellery tutor at Central School of Arts and Crafts in London.

Although never a household name, he has always enjoyed a high level of respect from other artists. From 1951 to 1974 the Davie family spent summer in Cornwall and Davie knew most of the second generation St. Ives group: Patrick Heron, Terry Frost, Bryan Winter, Peter Lanyon, and Paul Feile. Davie met Willem de Kooning, Jackson Pollock, Robert Motherwell and others in New York in 1956. By 1959, Davie had held solo shows in New York (1956) and at the Whitechapel in London (1958), been bought by the Museum of Modern Art and the Tate, and heralded by The Times as ‘an artist who bids to be recognized as the most remarkable British painter to have emerged in recent years’ (6th March, 1958).

During the 1960s and '70s Davie explored his new found passion for gliding, completing over 2000 hours of flying. He found 'a sort of mysterious realm away from everyday reality, one very close to natural forces', as he put it, that was analogous to painting.

Alan Davie at work in his studio in the 1950s (left) and his studio in the late 1990s. Photos: copyright of the artist.

Davie is fascinated by the art of other cultures. He sees within them a less materialistic life and a greater emphasis on spirituality. His art making process is not a practice that involves the production of art-objects for public appraisal or consumer demand, but one that seeks to unify the artist with a more spiritual existence.

As his art has developed, Davie has evolved how he uses improvisation within his work. Like Miro’s use of automatic drawing as a design for a painting, Davie’s later works are often more likely to be based on an intuitive sketch than constructed through the painting process directly on the canvas. In a 1993 interview with Art Review magazine he said of this process:

You can’t deny consciousness completely. You must have rules. Without a system you can perhaps achieve a beautiful chaos which is itself exciting up to a point, but it’s not until we impose restrictions on ourselves that important things begin to happen.[1 (Art Review, May 1993, (vol. XLV) p4.)

The images that Davie use are part of a wider ranging interest in the ‘other’ and the exotic. From his Zen Buddhism, through his Jazz playing and his gliding, Davie seeks experiences and ways of being that are intuitive and in some way ‘freer’.

Art is an intimate meditation process involving some kind of communion with the gods, it’s got nothing to do with communing with the public, as if it was some kind of show business. Art can exist without the public. I’m not interested in what anybody else thinks. I’m in it entirely for myself, and if someone else is on the same wavelength all well and good; if not, then forget it. But art should give people a kind of uplift, an understanding of the mystery of life itself. It should take people out of their mere selves into another realm. What one should get from art is a kind of inspiration and revelation. You should be taken out of yourself and lifted of the ground.”(ibid. p4.)

Davie continues to work in his home in Hertfordshire.

You can view a number of his works by Alan Davie across his career on the Tate website.

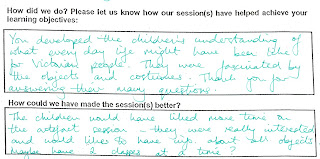

Since the museum closed for redevelopment in October 2010, our education team haven’t been able to have schools come and spend the day at the museum. However, this hasn’t stopped them keeping busy. They have taken their programme on the road, visiting schools within a 1 hour radius, bringing artefacts, costume and lots of fun along with them. Here is some of the feedback we’ve received from children and teachers.

Since the museum closed for redevelopment in October 2010, our education team haven’t been able to have schools come and spend the day at the museum. However, this hasn’t stopped them keeping busy. They have taken their programme on the road, visiting schools within a 1 hour radius, bringing artefacts, costume and lots of fun along with them. Here is some of the feedback we’ve received from children and teachers.

EDWARD WADSWORTH, A.R.A. (1889-1949)

EDWARD WADSWORTH, A.R.A. (1889-1949)